Every year in the UK, 3,000 people’s sight is damaged by a condition called giant cell arteritis. The symptoms can appear very suddenly and end in irreversible blindness. Dr Saleyha Ahsan met a group of people who’ve been affected and explains what to look out for.

“My mother in law lost a lot of weight, she was very low mood, very painful scalp, jaw pain - and when I say painful scalp, brushing her hair became impossible,” says Amanda Bartlett.

“Within the four hours that we were in eye casualty, towards the end she reached round her chair and grabbed my hand and said ‘Amanda, I can’t see anything.’ And she lost her sight that afternoon.”

Another woman tells me she felt “jaw ache, neck ache, earache and painful shoulders”. It culminated in a “sort of flash in one eye, and I actually lost the sight in this eye for about three minutes”.

At first, some people mistake the symptoms for a migraine - one describes it as “a cap of pain like my brain was being squeezed”.

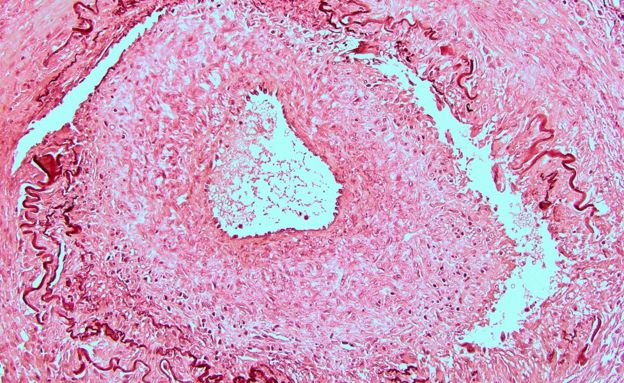

But these are all classic signs of giant cell arteritis (GCA). It occurs when arteries in the head and neck become inflamed and giant cells accumulate in the artery walls.

One of the arteries commonly affected provides blood to the optic nerve, which transmits information from the retina to the brain. Blocking the nerve and starving it of blood can cause permanent blindness.

The window of treatment is small - in some cases, sight can be lost within days or even hours. The only thing that can save it is immediate treatment with steroids.

Red flags:

Severe, often sudden headaches not relieved by painkillers - they tend to affect one side of the head or temples

Tenderness to the head and scalp - brushing hair can be painful

Swollen temporal arteries visible to the naked eye

Jaw pain especially when talking and chewing

Vision problems including double vision, blurred vision and sight loss in one or both eyes

The symptoms of GCA usually develop quickly but there may be earlier warning signs such as weight loss, day and night sweats, tiredness, mild fever, loss of appetite and depression.

It is related to another, less serious, condition called polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) which causes muscular pain and immobility. These illnesses can appear independently but often come together. GCA affects about a tenth of people with PMR in the UK.

GCA tends to affect adults over 50 and is three times more common in women than in men. It’s also seven times more common in white people than in black or Asian people.

In order to reduce the number of people losing their sight from GCA, the NHS has set up a new system to make sure people are diagnosed as quickly as possible. In some parts of the UK there are now dedicated phone lines so GPs can get patients an appointment with a rheumatologist within 24 hours.

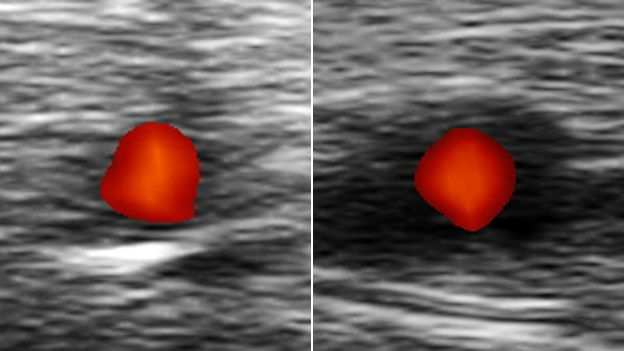

Anyone at risk is then screened using ultrasound - if a patient has GCA, the scan will reveal a dark band, known as the halo sign, around the temporal artery.

This fast-track system, pioneered by consultant rheumatologist Prof Bhaskar Dasgupta in 2013 at Southend University Hospital, saved Roger Keay’s sight.

“He recognised the condition immediately,” says Roger. “He did an ultrasound test and showed me on the screen - it saved my sight. I’m a very lucky man. If I had a million pounds I’d give it to him.”

In Southend, this approach cut the number of cases of full or partial sight loss from 17 a year to one in the year the trial was carried out - and that one was a referral from outside the area.

But it’s not just doctors who need to be aware of the signs of GCA and I would encourage everyone to heed the warning of one of my lecturers at medical school. His words have stuck with me with superglue-like ferocity for the past 10 years: “Beware the patient who complains of their scalp hurting when combing their hair.”